一 : 拉长回忆,思绪绵绵

流年匆匆,往事如烟。捏一把拉长了的回忆,思绪绵绵……——题记

交错的记忆,被红尘的风雨镌刻成沉默的雕像,静坐的身躯已布满了岁月的尘埃和忧郁的斜阳。或许,密封的心事无法遮住那回眸的眼神,在孤独增生、怀想绵绵的日子里,总是不时地回望远方。

往事如烟,轻轻地掠过乍暖还寒的心湖,一道道细节的涟漪在浅浅的眷思中荡漾,飘逸出淡淡的春愁;在被春意刚刚点绿的背景后,仿佛有似曾相识的笛韵在流淌。而此时,悠闲散步的风,却送来了一抹料峭的春寒,无意中撩起了未曾孵化的笙歌,瞬间扯起了千丝万缕的回味,是苦?是甜?是悲?是喜?

在这感慨的瞬间,回溯几千年的大千:普罗米修斯的善良与执着同样能感动上苍,尽管镶嵌石子的铁环记录着囚禁的伤痛,但自由的脚步依旧可以笑傲于天地间;常叹吴刚,既然想修道成仙,却又因何为情所伤,一时动怒,被流放到蟾宫伐桂,日日夜夜挥舞着斧头,却砍不尽千年的遗恨。

穿过时空的隧道,一切一切都远去了;一尊芳酒,曾几度醉倒梅边吹笛的人儿;幽香的笔墨,曾激起多少灵感的浪花;而如今,让人怀恋的田园,又荒芜了多少翠绿的诗行。

如果没有当初幽咽如泣的古筝弦鸣,优美的舞姿或许不会在依恋的台前上演。一枚枚心愿的纸船挽着时光,载走了昨日的溪边梦影;当过往的美丽乘着月华而去,怀想的烛火,催下了多少盈盈的红泪!虚掩的香屏已被黄昏覆盖,一帘风絮卷着生满青苔的故事,连同那浅绿色的情节,均已成为了池南旧事。( 文章阅读网:www.61k.com )

当清瘦的淡月苦吻着浮动的云片时,一首首千年的忧思几乎开遍了所有的季节。或许,无法凌驾轮回的神谕,许多梦,只能幻化成一缕缕隔世的云烟,缭绕于遗憾的碑前…

二 : 被世界遗忘的天才:特斯拉回忆录

This file may be freely redistributed as long as the original wording is not modified.

My Inventions

Nikola Tesla's Autobiography

At the age of 63 Tesla tells the story of his creative life.

First published in 1919 in the Electrical Experimenter magazine

Table of Contents

I. My Early Life

II. My First Efforts At Invention

III. My Later Endeavors

IV. The Discovery of the Tesla Coil and Transformer

V. The Magnifying Transmitter

VI. The Art of Telautomatics

I. My Early Life

The progressive development of man is vitally dependent on invention. It is the most important product of his creative brain. Its ultimate purpose is the complete mastery of mind over the

material world, the harnessing of the forces of nature to human needs. This is the difficult task of the inventor who is often misunderstood and unrewarded. But he finds ample compensation in the pleasing exercises of his powers and in the knowledge of being one of that exceptionally privileged class without whom the race would have long ago perished in the bitter struggle against pitiless elements.

Speaking for myself, I have already had more than my full measure of this exquisite enjoyment, so much that for many years my life was little short of continuous rapture. I am credited with

being one of the hardest workers and perhaps I am, if thought is the equivalent of labor, for I have devoted to it almost all of my waking hours. But if work is interpreted to be a definite performance in a specified time according to a rigid rule, then I may be the worst of idlers. Every effort under compulsion demands a sacrifice of life-energy. I never paid such a price. On the contrary, I have thrived on my thoughts.

In attempting to give a connected and faithful account of my activities in this series of articles which will be presented with the assistance of the Editors of the ELECTRICAL EXPERIMENTER and are chiefly addrest to our young men readers, I must dwell, however reluctantly, on the impressions of my youth and the circumstances and events which have been instrumental in determining my career.

Our first endeavors are purely instinctive, promptings of an imagination vivid and undisciplined. As we grow older reason asserts itself and we become more and more systematic and designing. But those early impulses, tho not immediately productive, are of the greatest moment and may shape our very destinies. Indeed, I feel now that had I understood and cultivated instead of

suppressing them, I would have added substantial value to my bequest to the world. But not until I had attained manhood did I realize that I was an inventor.

This was due to a number of causes. In the first place I had a brother who was gifted to an extraordinary degree—one of those rare phenomena of mentality which biological investigation has failed to explain. His premature death left my parents disconsolate. We owned a horse which had been presented to us by a dear friend. It was a magnificent animal of Arabian breed, possest of almost human intelligence, and was cared for and petted by the whole family, having on one occasion saved my father's life under remarkable circumstances. My father had been called one winter night to perform an urgent duty and while crossing the mountains, infested by wolves, the horse became frightened and ran away, throwing him violently to the ground. It arrived home bleeding and exhausted, but after the alarm was sounded immediately dashed off again, returning to the spot, and before the searching party were far on the way they were met by my father, who had recovered consciousness and remounted, not realizing that he had been lying in the snow for several hours. This horse was responsible for my brother's injuries from which he died. I witnest the tragic scene and altho fifty-six years have elapsed since, my visual impression of it has lost none of its force. The recollection of his attainments made every effort of mine seem dull in comparison.

Anything I did that was creditable merely caused my parents to feel their loss more keenly. So I grew up with little confidence in myself. But I was far from being considered a stupid boy, if I am to judge from an incident of which I have still a strong remembrance. One day the Aldermen were passing thru a street where I was at play with other boys. The oldest of these venerable gentlemen—a wealthy citizen—paused to give a silver piece to each of us. Coming to me he suddenly stopt and commanded, "Look in my eyes." I met his gaze, my hand outstretched to receive the much valued coin, when, to my dismay, he said, "No, not much, you can get nothing from me, you are too smart." They used to tell a funny story about me. I had two old aunts with

wrinkled faces, one of them having two teeth protruding like the tusks of an elephant which she buried in my cheek every time she kist me. Nothing would scare me more than the prospect of being hugged by these as affectionate as unattractive relatives. It happened that while being carried in my mother's arms they asked me who was the prettier of the two. After examining their faces intently, I answered thoughtfully, pointing to one of them, "This here is not as ugly as the other."

Then again, I was intended from my very birth for the clerical profession and this thought

constantly opprest me. I longed to be an engineer but my father was inflexible. He was the son of an officer who served in the army of the Great Napoleon and, in common with his brother, professor of mathematics in a prominent institution, had received a military education but,

singularly enough, later embraced the clergy in which vocation he achieved eminence. He was a very erudite man, a veritable natural philosopher, poet and writer and his sermons were said to be as eloquent as those of Abraham a Sancta-Clara. He had a prodigious memory and

frequently recited at length from works in several languages. He often remarked playfully that if some of the classics were lost he could restore them. His style of writing was much admired. He penned sentences short and terse and was full of wit and satire. The humorous remarks he made were always peculiar and characteristic. Just to illustrate, I may mention one or two instances. Among the help there was a cross-eyed man called Mane, employed to do work around the farm. He was chopping wood one day. As he swung the axe my father, who stood nearby and felt very uncomfortable, cautioned him, "For God's sake, Mane, do not strike at what you are looking but at what you intend to hit." On another occasion he was taking out for a drive a friend who carelessly permitted his costly fur coat to rub on the carriage wheel. My father reminded him of it saying, "Pull in your coat, you are ruining my tire." He had the odd habit of talking to himself and would often carry on an animated conversation and indulge in heated

argument, changing the tone of his voice. A casual listener might have sworn that several people were in the room.

Altho I must trace to my mother's influence whatever inventiveness I possess, the training he

gave me must have been helpful. It comprised all sorts of exercises—as, guessing one another's thoughts, discovering the defects of some form or expression, repeating long sentences or performing mental calculations. These daily lessons were intended to strengthen memory and reason and especially to develop the critical sense, and were undoubtedly very beneficial.

My mother descended from one of the oldest families in the country and a line of inventors. Both her father and grandfather originated numerous implements for household, agricultural and other uses. She was a truly great woman, of rare skill, courage and fortitude, who had braved the

storms of life and past thru many a trying experience. When she was sixteen a virulent pestilence swept the country. Her father was called away to administer the last sacraments to the dying and during his absence she went alone to the assistance of a neighboring family who were stricken by the dread disease. All of the members, five in number, succumbed in rapid succession. She bathed, clothed and laid out the bodies, decorating them with flowers according to the custom of the country and when her father returned he found everything ready for a Christian burial. My mother was an inventor of the first order and would, I believe, have achieved great things had she not been so remote from modern life and its multifold opportunities. She invented and

constructed all kinds of tools and devices and wove the finest designs from thread which was spun by her. She even planted the seeds, raised the plants and separated the fibers herself. She worked indefatigably, from break of day till late at night, and most of the wearing apparel and furnishings of the home was the product of her hands. When she was past sixty, her fingers were still nimble enough to tie three knots in an eyelash.

There was another and still more important reason for my late awakening. In my boyhood I

suffered from a peculiar affliction due to the appearance of images, often accompanied by strong flashes of light, which marred the sight of real objects and interfered with my thought and action. They were pictures of things and scenes which I had really seen, never of those I imagined. When a word was spoken to me the image of the object it designated would present itself vividly

to my vision and sometimes I was quite unable to distinguish whether what I saw was tangible or not. This caused me great discomfort and anxiety. None of the students of psychology or physiology whom I have consulted could ever explain satisfactorily these phenomena. They seem to have been unique altho I was probably predisposed as I know that my brother

experienced a similar trouble. The theory I have formulated is that the images were the result of a reflex action from the brain on the retina under great excitation. They certainly were not

hallucinations such as are produced in diseased and anguished minds, for in other respects I was normal and composed. To give an idea of my distress, suppose that I had witnest a funeral or some such nerve-racking spectacle. Then, inevitably, in the stillness of night, a vivid picture of the scene would thrust itself before my eyes and persist despite all my efforts to banish it.

Sometimes it would even remain fixt in space tho I pushed my hand thru it. If my explanation is correct, it should be able to project on a screen the image of any object one conceives and make it visible. Such an advance would revolutionize all human relations. I am convinced that this wonder can and will be accomplished in time to come; I may add that I have devoted much thought to the solution of the problem.

To free myself of these tormenting appearances, I tried to concentrate my mind on something

else I had seen, and in this way I would of ten obtain temporary relief; but in order to get it I had to conjure continuously new images. It was not long before I found that I had exhausted all of those at my command; my "reel" had run out, as it were, because I had seen little of the world—only objects in my home and the immediate surroundings. As I performed these mental operations for the second or third time, in order to chase the appearances from my vision, the remedy gradually lost all its force. Then I instinctively commenced to make excursions beyond the limits of the small world of which I had knowledge, and I saw new scenes. These were at first very blurred and indistinct, and would flit away when I tried to concentrate my attention upon them, but by and by I succeeded in fixing them; they gained in strength and distinctness and finally assumed the concreteness of real things. I soon discovered that my best comfort was attained if I simply went on in my vision farther and farther, getting new impressions all the time, and so I began to

travel—of course, in my mind. Every night (and sometimes during the day), when alone, I would start on my journeys—see new places, cities and countries—live there, meet people and make friendships and acquaintances and, however unbelievable, it is a fact that they were just as dear to me as those in actual life and not a bit less intense in their manifestations.

This I did constantly until I was about seventeen when my thoughts turned seriously to invention. Then I observed to my delight that I could visualize with the greatest facility. I needed no models, drawings or experiments. I could picture them all as real in my mind. Thus I have been led unconsciously to evolve what I consider a new method of materializing inventive concepts and ideas, which is radically opposite to the purely experimental and is in my opinion ever so much more expeditious and efficient. The moment one constructs a device to carry into practise a

crude idea he finds himself unavoidably engrost with the details and defects of the apparatus. As he goes on improving and reconstructing, his force of concentration diminishes and he loses sight of the great underlying principle. Results may be obtained but always at the sacrifice of quality.

My method is different. I do not rush into actual work. When I get an idea I start at once building it up in my imagination. I change the construction, make improvements and operate the device in my mind. It is absolutely immaterial to me whether I run my turbine in thought or test it in my shop. I even note if it is out of balance. There is no difference whatever, the results are the same. In this way I am able to rapidly develop and perfect a conception without touching

anything. When I have gone so far as to embody in the invention every possible improvement I can think of and see no fault anywhere, I put into concrete form this final product of my brain. Invariably my device works as I conceived that it should, and the experiment comes out exactly as I planned it. In twenty years there has not been a single exception. Why should it be otherwise? Engineering, electrical and mechanical, is positive in results. There is scarcely a

subject that cannot be mathematically treated and the effects calculated or the results determined beforehand from the available theoretical and practical data. The carrying out into practise of a crude idea as is being generally done is, I hold, nothing but a waste of energy, money and time.

My early affliction had, however, another compensation. The incessant mental exertion

developed my powers of observation and enabled me to discover a truth of great importance. I had noted that the appearance of images was always preceded by actual vision of scenes under peculiar and generally very exceptional conditions and I was impelled on each occasion to locate the original impulse. After a while this effort grew to be almost automatic and I gained great

facility in connecting cause and effect. Soon I became aware, to my surprise, that every thought I conceived was suggested by an external impression. Not only this but all my actions were prompted in a similar way. In the course of time it became perfectly evident to me that I was merely an automaton endowed with power of movement, responding to the stimuli of the sense organs and thinking and acting accordingly. The practical result of this was the art of

telautomatics which has been so far carried out only in an imperfect manner. Its latent

possibilities will, however, be eventually shown. I have been since years planning self-controlled automata and believe that mechanisms can be produced which will act as if possest of reason, to a limited degree, and will create a revolution in many commercial and industrial departments.

I was about twelve years old when I first succeeded in banishing an image from my vision by wilful effort, but I never had any control over the flashes of light to which I have referred. They were, perhaps, my strangest experience and inexplicable. They usually occurred when I found myself in a dangerous or distressing situation, or when I was greatly exhilarated. In some instances I have seen all the air around me filled with tongues of living flame. Their intensity, instead of diminishing, increased with time and seemingly attained a maximum when I was about twenty-five years old. While in Paris, in 1883, a prominent French manufacturer sent me an invitation to a shooting expedition which I accepted. I had been long confined to the factory and the fresh air had a wonderfully invigorating effect on me. On my return to the city that night I felt a positive sensation that my brain had caught fire. I saw a light as tho a small sun was located in it and I past the whole night applying cold compressions to my tortured head. Finally the flashes diminished in frequency and force but it took more than three weeks before they wholly subsided. When a second invitation was extended to me my answer was an emphatic NO!

These luminous phenomena still manifest themselves from time to time, as when a new idea opening up possibilities strikes me, but they are no longer exciting, being of relatively small

intensity. When I close my eyes I invariably observe first, a background of very dark and uniform blue, not unlike the sky on a clear but starless night. In a few seconds this field becomes

animated with innumerable scintillating flakes of green, arranged in several layers and advancing towards me. Then there appears, to the right, a beautiful pattern of two systems of parallel and closely spaced lines, at right angles to one another, in all sorts of colors with yellow-green and gold predominating. Immediately thereafter the lines grow brighter and the whole is thickly sprinkled with dots of twinkling light. This picture moves slowly across the field of vision and in about ten seconds vanishes to the left, leaving behind a ground of rather unpleasant and inert grey which quickly gives way to a billowy sea of clouds, seemingly trying to mould themselves in living shapes. It is curious that I cannot project a form into this grey until the second phase is reached. Every time, before falling asleep, images of persons or objects flit before my view. When I see them I know that I am about to lose consciousness. If they are absent and refuse to come it means a sleepless night.

To what an extent imagination played a part in my early life I may illustrate by another odd

experience. Like most children I was fond of jumping and developed an intense desire to support myself in the air. Occasionally a strong wind richly charged with oxygen blew from the mountains rendering my body as light as cork and then I would leap and float in space for a long time. It was a delightful sensation and my disappointment was keen when later I undeceived myself.

During that period I contracted many strange likes, dislikes and habits, some of which I can trace to external impressions while others are unaccountable. I had a violent aversion against the earrings of women but other ornaments, as bracelets, pleased me more or less according to design. The sight of a pearl would almost give me a fit but I was fascinated with the glitter of

三 : 《被世界遗忘的天才(特斯拉回忆录)》——新书推荐

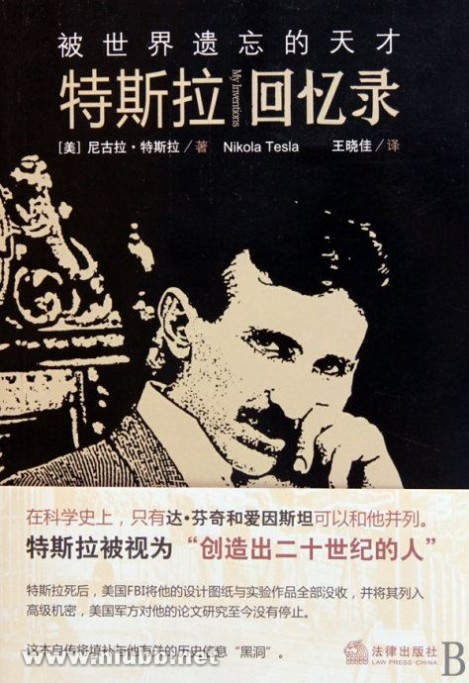

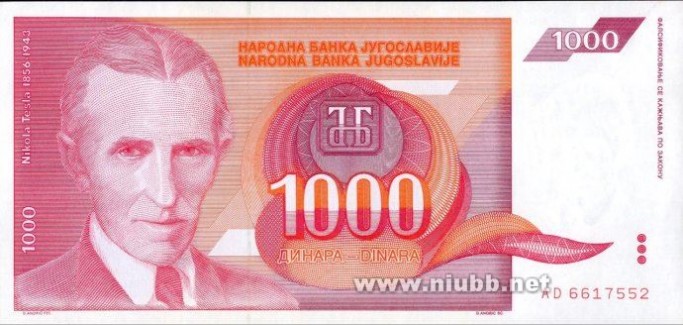

《被世界遗忘的天才(特斯拉回忆录)》——新书推荐书名:《被世界遗忘的天才(特斯拉回忆录)》

作者:(美) 尼古拉•特斯拉

译者:王晓佳

法律出版社ISBN:97875118077932010-07-01第1版2010-07-01第1次印刷

开 本:32开页数:124页类别:历史.地理 -> 历史 -> 传记

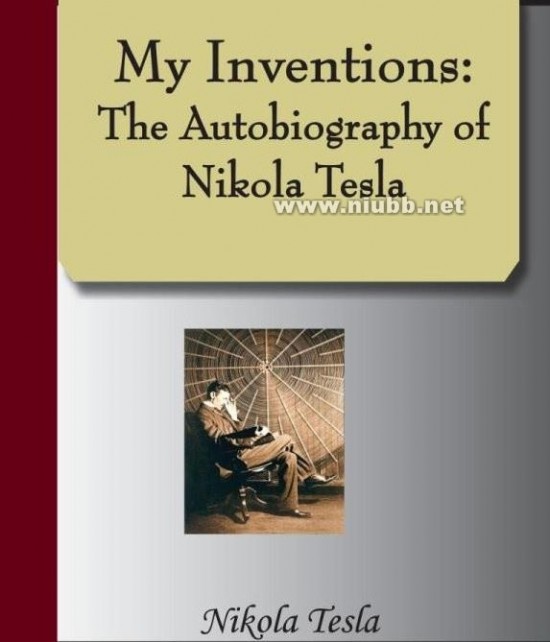

《My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla》(《我的发明:尼古拉.特斯拉自传》)一书由BenJohnson编辑,详述了尼古拉.特斯拉的工作。本书内容大部分源自尼古拉.特斯拉于1919年给《电学实验者杂志》写的一系列文章,当时特斯拉63岁。

《被世界遗忘的天才:特斯拉回忆录》是《My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla》的中文译本。这是特斯拉自己的传记,特斯拉是一个科学家,不是一个文学家,虽然他很爱好文学。他不可能事无巨细的把自己的一生写下来。 特斯拉写这本传记可能有这样两个目的:1.讲述自己奇异的经历和感受,以便后人研究。2.对自己的发明的前因后果,以及他希望后人继续努力的方向。

只知道写垃圾论文的中国的大学物理学教授们、以及只知道考分和应试教育的中学物理学高级教师们都不知道特斯拉的事迹,CCTV10的人物播出特斯拉的专辑后,电视让特斯拉突然出现在国人眼前,能及时出这本书还是相当有必要的,至少给读者提供了最为基本的资料。

这本书是特斯拉本人的语气,读者能感受得到,特斯拉的灵魂还是个很顽皮的孩子,一直享受着他在创造中的玩耍、嬉戏。中文翻译还是蛮到位的。

一位既有文化又有正义感的网友看了我的张卫民新浪博客介绍特斯拉的博文后发表评论:“我是一名在读的工学硕士,我学的就是电力系统、高压输电,我作为本专业的研究生,竟然连交流电的始祖尼古拉•特斯拉的贡献都不清楚,可见科学受其他因素的毒害有多大!我完全得不到这方面的信息。我汗颜!特斯拉绝对是一个能让我们顶礼膜拜的科学巨匠!我这个专业,大学第一堂课就应该单独讲他。他应该是每个工科学生的真正的偶像!但是,课本里没有他,外文文献里也没有他。对人类有这么多贡献和灵感的人,不应该被后人遗忘,当今世界对特斯拉更不应该刻意予以埋没!”

《被世界遗忘的天才(特斯拉回忆录)》第一章 我的少年生活

人类的进步很大程度上依赖于发明创造。发明是人类智慧最重要的产物。其最终目的是以智慧控制物质世界;利用自然力满足人类需求。对于那些经常遭受误解,并得不到回报的发明家来说,这是一项艰巨的任务。然而,他们又得到了丰厚的精神补偿,在利用智慧进行发明创造的过程中获得了极大快乐,凶为拥有知识成为某些特权阶层,没有他们,面对残酷的自然环境,人类早就灭亡了。多年来,我一直体验着这种无上的快乐,一直沉浸在创造发明的持续满足之中。人们称赞我是最勤奋的人,如果思考也算劳动的话,或许的确如此,因为一天之中从睁开眼,我几乎一直在思考。但是,如果工作被认为是在特定时间,根据狭隘标准从事某些特定活动的话,那么或许我是最懒惰的家伙。

每一项被迫进行的工作都会牺牲生命能量。但是,这种现象从未在我身上出现过。相反,我越是思考,我的智慧就越丰富。为了使这本传记中记录的人生经历连贯且令人信服,尽管很不情愿,我必须讲述一下自己年轻时期所受的影响、所处的环境和经历的事件,它们对我确立自己的职业生涯具有至关重要的作用。人们幼年时期的活动都是在纯粹的本能驱使下进行的,充满活力而又无拘无束。随着年龄的增长,理性不断得到强化,我们也会变得越来越有条理有计划。那些早期的冲动,尽管没有马上产生成效,但却是最伟大的,甚至可能决定我们的命运。事实上,我现在认为,假如我幼年时期充分理解并培养而并非压制这些冲动,我将对世界做出更大的贡献。但是,直到成年以后,我才真正意识到自己是一个发明家。

这一过程之所以有些曲折,原因是多方面的。首先,我有一个才华横溢的哥哥,他是罕见的天才,即使生物研究也很难解释清楚。他的过早去世使我的人问父母终日郁郁寡欢(关于“人间父母”的说法,我会在后面做出解释)。我们家有匹马,是好友送给我们的礼物。这是一匹高贵的阿拉伯纯种马,非常通人性,它曾在极其危险的情况下救了我父亲的命,因此深得全家人的宠爱。

一个寒冷的冬夜,我父亲被人叫去做紧急法事,途经常有狼群出没的深山时,马受了惊吓,将父亲重重地摔倒在地,狂奔而去。回到家时,它已是伤痕累累,筋疲力尽。但是,在向我们发出警报之后,它又马上冲了出去,返回事发地点将已经恢复意识,却不知自己已在雪地里躺了几个小时的父亲驮了回来。返家途中,他们碰上刚刚前来搜救的人群。这匹马弄伤了我的哥哥,并最终导致他离世。我亲眼目睹了那场惨剧,尽管事情已经过去了很多年,它在我脑海中留下的印象丝毫没有减弱。在我的记忆中,哥哥实在太出色了,跟他相比,我所有的努力都显得黯然失色。我做出任何值得称道的事情,都只能加重他们对失去哥哥的痛苦。所以,我幼年时期是很缺乏自信的。

但是,假如从一件我至今仍记忆犹新的事情来判断的话,我绝对不是笨小孩。一天,我正和其他孩子在大街上玩耍,一群市政官走了过来。在这群受人尊敬的绅士当中,那位最年长的富人在我们面前停下来,送给每个小孩一枚银币。但是,当他走到我跟前时,突然命令道:“看着我的眼睛。”我看着他的眼睛,伸出手去,准备接那枚珍贵的硬币。令我沮丧的是,他说:“不,没有了,你从我这里得不到任何东西。你太聪明了。”

人们总是喜欢谈论我的一件趣事。我有两位满脸皱纹的姑姑,其中一位长着两颗龅牙,活像象牙。每当她亲吻我时,牙齿就会深深刺痛我的脸。没有什么能比这些充满慈爱的“丑”亲戚更让我感到恐惧的了。一天,母亲抱着我,她们问我哪位姑姑更漂亮。认真端详她们的脸之后,我若有所思地指着其中一个说:“她没有那个丑。”

此外,从出生那一刻起,家人就希望我将来能子承父业,做一名牧师,这个想法一直困扰着我。我只想做工程师,父亲却坚持己见,寸步不让。我爷爷是拿破仑时期的一名军官,他还有个兄弟是一所著名大学的数学教授,他们从小就接受了军事教育。然而,令人不解的是,父亲后来却成了牧师,并获得了相当高的名望。我父亲非常博学,是一位名副其实的自然哲学家、诗人、作家。据说,他布道时口才跟亚伯拉罕•阿•桑克塔•克拉拉(Abrahama-Sancta-Clara)一样好。他有着惊人的记忆力,常常可以用几种语言大段大段地背诵经典著作。他常常风趣地说,如果一些经典绝版,他完全可以依靠记忆把它们重新默写出来。父亲的写作风格更是受到大家的赞誉。他笔下的句子简洁明快,充满着智慧和幽默。他写出的内容总是诙谐幽默、见解独到。简单举例说明的话,或许我可以讲一两个买例。

在仆人当中,有一个眼睛斜视的人叫梅恩(Mane),他被雇来在农场一带工作。一天,梅恩正在劈柴。正当他挥动斧头的时候,站在旁边的父亲感到非常不安,于是警告说:“看在上帝的分上,梅恩,不要砍你看到的东西,要砍你想要击中的东西。”

还有一次,父亲驾车出去兜风,一个朋友不小心将自己昂贵的皮大衣蹭到了车轮上。我父亲提醒他说:“注意你的大衣,你会把我的车轮弄坏的。”

父亲有一个自言自语的古怪习惯,他经常独自一人变换着语调展开生动的谈话,并纵情地激烈辩论。如果恰巧有人在附近听到,肯定以为房间里有几个人正在起劲地辩论。

尽管追本溯源,我的创造能力与母亲的影响息息相关,但父亲对我的培养也是有一定益处的。这些培养包括各种各样的训练,比如:推测他人的想法、发现某种表达方式的欠缺、背诵长句或练习心算。这些日常训练是为了增强记忆力和推理能力,尤其是提高判断力,毫无疑问,这些训练对我日后的发展产生了巨大的积极作用。

我的母亲出生于农村的旧式家庭,有几位家族成员是发明家。她的父亲和祖父曾为家人发明了很多工具,用于家庭生活、农业生产或其他用途。母亲是一位名副其实的伟大女性,她能力非凡,性格勇敢、刚毅,勇敢地面对生活中的风风雨雨,经历过许多艰辛与苦难。在她16岁时,一场可怕的瘟疫席卷了整个地区。外祖父被人叫去给垂死的病人授临终圣餐礼,他不在家时,母亲独自到已经染上重病、奄奄一息的邻居家帮忙。她为已逝者沐浴、更衣并陈设尸体,并且按照当地的风俗用鲜花给他们做装饰,等外祖父返回村庄的时候,他发现我母亲已经为基督教葬礼做好了一切准备。

特斯拉母亲发明的纺织机械

特斯拉母亲发明的纺织机械

我母亲是一流的发明家,我相信,如果她不是远离现代生活,能接触众多机会的话,她一定能有很多伟大的发明。她发明和制作了各种工具和设备,并用自己纺的棉线编织精美的图案。她甚至亲自播种、培育植物,然后亲手提取纤维。她每天都会从黎明工作到深夜,忙个不停,家人的衣服和屋里的家具陈设,大部分都出自母亲的双手。她年过60以后,手指仍然非常灵巧,甚至可以在一根眼睫毛上打三个结。

我的迟迟觉醒,还有另外一个更为重要的原因。我少年时期,经常受到眼前一种奇特景象的折磨,它们的出现往往伴随着强光,破坏我的视力,使我看不清真正的物体,并且干扰我的思想和行动。那些呈现在我眼前的景象,根本不是自己的主观臆想,都是我以前实际看到过的。当有人跟我说起一个词的时候,那个词特指的景象就会栩栩如生地浮现在我眼前,有时我根本无法判断自己看到的事物是否真实存在。这让我极为不适和惊恐不安。我请教过很多生理学和心理学方面的专业人士,却没有一个人可以圆满地解释这一奇特现象。这些现象似乎是独一无二的,但我这种想法或许过于武断,因为我知道哥哥以前也曾经遇到过同样的问题。我自己得出的理论是这样的:这些景象是高度兴奋状态下,大脑对视网膜产生的反射作用。它们绝对不是疾病或精神痛苦导致的幻觉,因为我在其他方面都很正常,情绪也很平静。举例来说,当我看到葬礼或其他刺激性场景时,我就会遭遇这种痛苦。一旦夜深人静,那些景象便会纷至沓来,在我的眼前活灵活现,即使我想尽一切办法仍不能将它们驱散。如果我的理论是正确的,那么我们就有可能将人们想象的任何物体图像投射到屏幕上,让所有人看到。如果此预见成为现实,它将导致人与人关系的革命性变化。我坚信,这个奇迹可能而且必将在今后的某个时间实现。附带说明一下,我已经对此问题进行了大量思考。

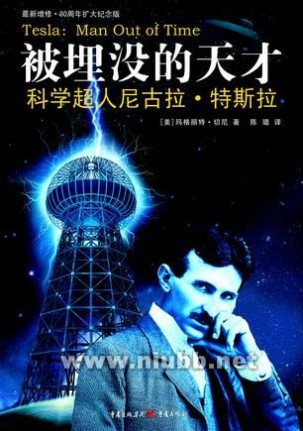

特斯拉自传英文版封面

特斯拉自传中文版封面

欢迎愿意了解科学超人尼古拉.特斯拉的网友到书店阅读浏览、到图书馆借阅。

“他是先知,他为人类做出了巨大的贡献,他开创了电气化时代...甚至早就预测(?制造?)通古斯大爆炸...或许他本来就不是地球人。”

《被埋没了的天才》内容简介

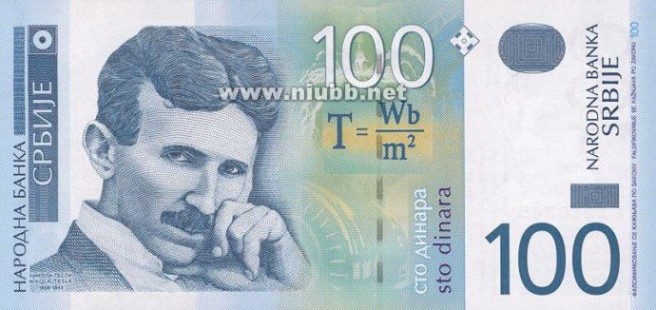

尼古拉•特斯拉被西方科学界的精英人物誉为是唯一堪比达•芬奇并超越爱因斯坦的伟大科学家,是人类有史以来最伟大的天才、发明创造的巨匠,但由于他身上同时也具有某种神秘甚至超自然的特质,也有人称他为神秘怪客或超人。是他发明和创造了交流电系统,对现代世界工业产生了深远影响。他在科学和工程学领域取得了大约1000项发明。他的很多研究项目,因为大大超前于时代,技术条件远远无法跟上,而难以在他的有生之年完成。迄今为止,全世界的科学发明体系仍然建立在特斯拉的遗产之上,是他“发明”了现代世界。

然而,因为历史上一些利益集团的阴谋,和美国军方一些更为神秘的理由,他的成就与事迹被人为地打压或隐瞒,以致绝大多绝普通人连他的名字都没有听说过。但随着人类对环境破坏的加大而引发出对清洁能源与自由能源(免费能源)的渴求,特斯拉的名字又再次浮出水面。

本书是西方关于特拉斯的众多著述中最权威也最畅销的一部。在本书中,作者对特斯拉奇特的命运与遭遇进行了深入研究,并将其详尽而生动地予以揭示。

在这部迄今为止最好的尼古拉•特斯拉传记中,玛格丽特•切尼发掘了这一位20世纪最伟大的科学家及发明家被埋没的、杰出而有预知能力的宏伟思想。尼古拉•特斯拉被他的敌人称作疯子,被钦服他的人称为天才,被世人公认为一个谜。而毫无疑问,他是一位开拓性的发明家,创造了一系列令人惊叹、甚至是让世界改头换面的装置。特斯拉不仅发现了旋转磁场——这是大多数交流电机器的基础,更将我们带向了机器人、计算机以及导弹科学的基本所在。然而,出乎所有人意料的是,所有这些装置的创造并无理论在先。他的天赋几乎是超自然的,他辉煌、热切燃烧的一生以及所有天才几乎都有的神经官能症,使其受扰于一系列的强迫症和恐惧症,并偏爱于铺张浪费的、凭脑海中的形象所见达成的试验方法。与此同时,他也是一位受人喜爱的社会人士,受到各色人等——包括马克•吐温和乔治•威斯汀豪斯等名人的钦佩,以及一大批社交名媛的爱慕。

从特斯拉出生于南斯拉夫,到20世纪40年代死于纽约,玛格丽特•切尼描绘了一位引人入胜的人物形象。按编年顺序探究的人物一生,是一种有效的方式,能给予我们生存其中的世界以持续不断的警示。本书深入探索了一位科学奇才仍有待于世人探究的成就,并调查了这位人物在科学之外所经历的种种困扰和古怪。

作者简介

玛格丽特•切尼是一位罕见的、作品内容全面的传记作家。关于特斯拉,她还和罗伯特•乌(RobertUth)合著有《特斯拉:闪电的主人》(Tesla:Master ofLightning)。此外,她写有伟大的歌舞表演者和歌者马伯尔•梅尔瑟(MabelMercer)的传记《马伯尔的午夜》(Midnight atMabel’s),以及《此时农场为何:美国连环杀人犯》(Meanwhile Farm and Why:The SerialKiller in America)。现居美国加州。

“非同寻常地生动……华丽,古怪,一种几乎超自然的天赋……尼古拉•特斯拉或许是世界上已知的最伟大的发明家……极其引人入胜。”

——伦敦《星期日泰晤士报》(The Sunday Times)

“一部优秀作品……是对近代科学史的重要贡献……内容翔实,读来令人愉快。”

——《美国科学家》(American Scientist)

“文献充分,富有同情心,非常有吸引力……是一部特斯拉的神奇事迹编年史。”

——《出版家周刊》(PublishersWeekly)

“切尼极好地记录了这位最具特殊气质、真正如谜一般的‘科学家’(也许是一位超人?)的一生,内容全面,文笔流畅……值得热心推荐。”

——《选择》(Choice)

“一个在现代科学史上富有远见的天才。”

——《伦敦海峡时报》(The Sunday Times, London)

“一幅戏剧性的、光彩夺目的特斯拉肖像。”

——《探索》(Discover)

“特斯拉是近100年以来一个魅力不可抗拒的主题,切尼非常出色地完成了它……成为众多同类书籍中的经典。”

——《柯克斯评论》(KirkusReviews)

不是所有的天才都叫特斯拉(brokenjade文)

有一种说法是:尼古拉·特斯拉不是史上最被高估的科学家,就是最被低估的科学家。根据特斯拉这位大仙现在的知名度来看,明摆着,他的确是被低估了,至于是不是那个最被低估的人,谁也说不清楚,因为这个发明狂人的一生中围绕了太多的迷团、传闻和阴谋。

相传特斯拉家拥有超强的天才基因,她的母亲虽然没受过什么教育,却也是个民间发明家,改良了许多家务工序。据说尼古拉并不是他们家最有天赋的,他一直声称他哥哥比他聪明不知多少倍,他对他哥哥的的崇拜如滔滔江水连绵不绝,然而这个天才哥哥却早早的夭亡了,有坊间秘闻说,在一次嬉戏中,尼古拉将他的哥哥失手推下楼梯。。。不管怎么说,特斯拉遗传了他家的优良基因,5岁时就发明了一种没有叶片的水车,十岁就上了中学,俨然就是一个方仲咏,只是方仲咏长大以后就残了,特斯拉不但没残,还将他的天赋发挥到了极致。

成年的特斯拉来到美国,可以肯定的是,特斯拉大仙是一枚标准的东欧帅锅,身材高大,举止优雅,气质高贵,穿着考究,会用英、法、德、斯拉夫语朗诵诗歌,备受社交圈内名媛青睐,换一般人早就堕落成卡萨诺瓦了,但特斯拉坚信,他的生命是要奉献给科学事业滴,结果居然真的终生未娶。但是特斯拉的人格魅力实在是太牛逼了,以至于明知道不会有结果,仍然有数量众多的大姑娘小媳妇,美正太怪蜀黍,以及。。。小动物无限爱慕他。最后,特斯拉与一只鸽子陷入了爱河,只要他走在曼哈顿的街头,鸽子们就会落在他的身上,即使他没有喂它们。特斯拉只要见到受伤或快要冻死的鸽子,就会抱回住处精心护理。可以这么说,特斯拉甚至比吴宇森更喜欢鸽子。

在这里我不想说特斯拉在科学上的成就,因为这个人在科学上有多大的成就根本没人说的清,由于他独特的思考方式,特斯拉几乎从不对自己的发明进行详尽的记录,一切都在他那颗发达的大脑里,加之与爱迪生集团间的龃龉,和不断被人盗用研究成果,特斯拉的后半生对于自己的发明更加注重保密。从目前已知的信息中,我们得知,特斯拉发明了交流电,并因此一直遭到爱迪生集团的迫害;他发明了无线电,却被马可尼盗用了,直到特斯拉逝世后,美国专利局才承认无线电的专利应属特斯拉;他早在伦琴之前几年,就照出了第一张X光照片(拍摄的对象是他的好友马克吐温,可是却照出了一根大螺丝钉。。。照妖镜么?);他设计了无人驾驶快艇,制造了垂直起落飞机,雷达,甚至还造出了远程导弹,那是在20世纪初,但是由于这些东西太科幻了,美国军方居然没能投入大规模生产。。。此外,他还提出了地球同步卫星的构想,因为资金原因,没能得以实施。但他毕竟还搞出了一些沿用至今的东西,比方说汽车计速器和空调系统。。。

二战后,特斯拉生前的研究资料与书籍成吨的被运往他的故乡南斯拉夫,注意,成吨。可是这些资料并非全部,特斯拉逝世后,他的遗物,包括实验室设施曾长期被美国联邦机构收管,之后十几年间,不断有资料神秘失踪,傻子都能明白是怎么回事,因为特斯拉生前曾研究过超级武器,这些武器的设计他从来没公开过。对于他发明的推测近些年来变得越来越神乎其神,06年克里斯托弗·诺兰有部很牛的片子叫ThePrestige《致命魔术》,两条线索,暗线讲的就是特斯拉与爱迪生之争。扮演特斯拉的也是个人物,大名鼎鼎的摇滚变色龙大卫鲍伊,片子最后,居然后无厘头的让特斯拉发明了克隆机。。。不过如果你了解过特斯拉的话,可能会想,既然是特斯拉,那真的有可能吧,这个人的想象力和创造力真的不是用地球人的逻辑可以解释的!

于是,有好事者开始鼓吹特斯拉是从外星来地球帮助人类的超级生物,这种论调甚至在特斯拉在世时就风行一时,老爷子自然是不肯承认,不过谁让他公开宣称存在外星人,自己还接收到过外星人的信号呢。。。1959年,一个传记作家出版了一本小册子,试图证明特斯拉是从金星上来的,而且很搞的用绿色油墨印刷。有关特斯拉拥有超能力的传闻还包括他幼年时期的几次见义勇为,据说大半夜的他听到火焰燃烧的声音,叫醒父母,父母却说什么声音也没有,特斯拉不放心的出门查看,发现邻居家着火了!超级外星生物特斯拉掌握着人类生死的大权!在纽约,特斯拉发明了一种振荡器,可以制造出不同程度的震动效果,马克吐温老爷爷很喜欢这个东西,经常央求特斯拉把那玩意接他玩玩,特斯拉不得不时刻看住这个老顽童,因为他的振荡器实在太危险了,在一次振荡器试验中,当时政府居然误以为是发生了地震,紧急疏散了居民。特斯拉说,只要他愿意,他可以用一个拳头大小的振荡器在十分钟内摧毁布鲁克林大桥,甚至,他可以用他的振荡器将地球震成两半。。。幸而,没人怀疑他,没人要他证明。

特斯拉不是完人,他脾气古怪,喜好奢华,狂妄而自负,即便如此,比起他的竞争对手爱迪生,他都更值得世人尊重。在这位所谓的发明大王的发明中,根本没有几项是爱迪生自己的原创作品,为了经济利益,他可以派人捣毁特斯拉的实验室,盗取别人的成果,他散布谣言,恶意中伤特斯拉和他的发明,他贿赂当局,使特斯拉的成果不能得以应用。没错,爱迪生和特斯拉都希望通过发明创作的商业化获得利益,但爱迪生赚钱是为了更多的钱,特斯拉却是为了进行更多的实验。每当纽约人点亮所有的灯来纪念爱迪生,却忘记了那个为他们提供了源源不断交流电电力能源的特斯拉时,我便感到阵阵恶寒。

四 : 特斯拉(NikolaTesla)回忆录_彩虹

本文标题:特斯拉回忆录-拉长回忆,思绪绵绵61阅读| 精彩专题| 最新文章| 热门文章| 苏ICP备13036349号-1