一 : Collaborative Maintenance of Collections Keep it Simple a Companion for Simple Wikipedia 1

1

Collaborative Maintenance of Collections:

Keep it Simple: a Companion for Simple Wikipedia ?

2

Collaborative Maintenance of Collections:

Keep it Simple: a Companion for Simple Wikipedia ?

Abstract

In this paper, we look at some of the ways in which the

community around Simple Wikipedia, an offspring of

Wikipedia – the notorious free online encyclopaedia –

manages the on-line collaborative production of reliable

knowledge. We focus here on how it keeps its

collection of articles ‘simple’ and easy to read. We find

that the labelling of pages as “unsimple” by core

members of the communities plays an important but yet

insufficient role. We suggest that the nature of this

mode of decentralized knowledge production and the

structure of Wiki-technology might demand for

implementing an editorial companion to the community.

3 Introduction

The question of collective knowledge production is getting more and more important for organizations and societies of the 21st century. All around the web, groups of people have started experimenting various ways to share, create, and maintain common pools of knowledge. After the success of open-source software, the recent and phenomenal success of Wikipedia has started attracting the attention of practitioners and policy makers: the former, because they believe that they can learn from Wikipedia more lessons about how to harness the collective intelligence and voluntary efforts of on-line communities, and the latter, because they are concerned not only with the viability and economic sustainability of such models, but also, increasingly, with the reliability and quality of information it contains.

Indeed, as soon as Wikipedia becomes, as it has already largely achieved, an authoritative source of contents on the web that is used on a daily basis by many students around the world, by business people within numerous private companies, and by civil servants in administrations, the reliability of its contents become of utmost importance, and the risk that errors could start propagating this way, unnoticed, becomes major.

We believe that we should admit that we don’t know what to do about Wikipedia and that, although we might be concerned about it and share for instance the concerns expressed for instance by Parnas and others (Denning et al., 2005), this is probably not enough. Wikipedia is there, and we suggest here that management scientists and scholars of other disciplines should now turn a more proactive attitude towards Wikipedia and related communities: that is, they should turn to explicitly studying what determines the quality of the information produced collectively and in a decentralized way by Wikipedia, and toward suggesting improvements and sending

4 more appropriate and informed warnings and toward offering deeper insights into the management of such on-line communities and knowledge repositories. Furthermore, we believe that this approach might also be a good strategy for organizations that closely observe these communities to extract insights that could be useful for them in the relationships that they are engaging with various kinds of on-line communities – first of all of users and customers1.

Based on an analysis of readability maintenance in Simple Wikipedia, an offspring of main Wikipedia that aims to be an encyclopaedia in plain and simpler English, we suggest that an artificial companion – a net of bots configured as a managerial and editorial assistant – could help Wikipedia compensate for part of the features that stem from its open, decentralized, and loosely coupled nature, while still harnessing the best characteristics of this emerging mode of knowledge production.

We will briefly outline first a few relevant elements of the history of Wikipedia. We will then present our empirical approach, and from this we will present results on three different grounds – labels, eyeballs, and bots & companions – by formulating preliminary lessons learnt from our analysis of reliability maintenance in Simple Wikipedia. We conclude by pointing out some of the necessary steps toward implementing a managerial and editorial companion to Wikipedia. 1 . In a sense, the recent focus on vandalism was only a forerunner of other, more important concerns, and was indeed relatively easily dealt with by ‘closing’ access to a very limited number of pages.

5 Background

Wikipedia was started in 2001 after Nupedia, an earlier attempt to create an open content encyclopaedia, had failed (Sanger, 2005). Nupedia had aimed to be a highly reliable, peer-reviewed resource. Everyone could submit articles, but before the articles were accepted they had to go through a seven-step review process. In practice, this process proved to be too burdensome and, comparatively, part of the success of Wikipedia is due to the ease with which people can participate. However, as Larry Sanger points out, there were important factors that played a role as well: “Wikipedia started with a handful of people, many from Nupedia. The influence of Nupedians was, I think, pretty important early on; […] All of these people, and several other Nupedia borrowings, had a good understanding of the requirements of good encyclopedia articles, and they were good writers and very smart. The direction that Wikipedia ought to go in was pretty obvious to myself and them, in terms of what sort of content we wanted. But what we did not have worked out in advance was how the community should be organized, and (not surprisingly) that turned out to be the thorniest problem. But the facts that the project started with these good people, and that we were able to adopt, explain, and promote good habits and policies to newer people, partly accounts for why the project was able to develop a robust, functional community and eventually to succeed.” Without the former Nupedia staff there to assume the roles of system integrator and co-ordinator, we wonder whether the take-off of Wikipedia would have been harder to achieve.

Soon after Wikipedia was initiatied – in October 2002 –, Derek Ramsey started to use a "bot" to add a large number of articles about United States towns; these articles were automatically generated from U.S. census data. Occasionally, similar bots had

6 been used before for other topics. These articles were generally well received, but some users criticized them for their uniformity and generally machine-like writing style. As time passed, other scripts bots appeared and took over an increasing pay-load for typical system-integrator tasks like the establishment and maintenance of links between Wikipedia project in different languages, other repetitive edits that would be extremely tedious to do manually. Occasionally bots are used for automatic content generation, but this is generally not encouraged.

Simple Wikipedia shares many organizational features with the main English Wikipedia. The most important difference is that Simple Wikipedia has the clearly defined goal of becoming an encyclopedia in plain English. Where the main Wikipedia has invented “featured articles” to encourage high quality writing, Simple Wikipedia has opted for flagging articles that are considered unsimple. Simple Wikipedia has no indigenous bots: there are bots from other projects but who just visit the Simple Wikipedia pages from time to time in order to keep links up to date. Finally, Simple Wikipedia is much smaller and less visible that the main Wikipedia.

Approach

Studies in the fields of linguistics and information science have already shown that interesting research can be done on Wikipedia using quantitative approaches (Stvilia et al., 2005). Trying to bring those approaches one step further into the realm of innovation studies and organizations sciences in the line of den Besten, Dalle & Galia (2006), our analysis of readability maintenance in the Simple Wikipedia collection here is mainly based on descriptive statistics of micro-data that we have been able to extra from the Simple Wikipedia archives.

7 Like its sister projects, complete archives of Simple Wikipedia are available from the web at downloads.wikimedia.org. These archives also serve as database backup dumps and contain the raw text sources of all versions of pages or articles that have ever been part of the collection and in addition the archives records for each page who edited it and when. The archive on which we base our analysis here is the “meta-history” archive of simplewiki of 6 September 2006. This archive contains information on more than 25 000 pages and almost 20 000 contributors who made a grand total of more than 170 000 edits on those pages.

In addition to basic information like page-number, version-number, and version-data, there are three types of information that we extract from the archive. First, for each version of each page in the collection, we check whether there is a string “{{unsimple}}” in the raw text. If this string is there, we know that that version of the page has been tagged with the label “unsimple”. Second, for each contributor to the collection, we try to determine his/her status first, by looking whether the contributor is identified by an ip-address, as is the case for anonymous contributors, and next, by matching his/her username and user-id with the usernames and user-ids that are assigned to the special groups in an auxiliary table that can be downloaded from the same web-site. We consider contributors that have not been assigned to a special group to be regular registered members and the contributors that have been assigned to a special group to be bots if the group is “bot” and administrator otherwise.

Finally, we compute are a readability score for each version of each page in the collection. We determine this readability score by counting the number of syllables per word and the number of words per sentence in the text using the standard well-know Flesch reading easy formula (score = 206.835 – 84.6*syllables/words –

1.1015*words/sentences). The score thus found score is a number between 0 and 100

8 that corresponds to a readability level range from very difficult to very easy as is illustrated in Table 1. The Flesch reading easy formula, which has been elaborated on the basis of school texts by Flesch in 1948, has been very popular, especially in the US, as a measure of plain English. Its popularity rests on the fact that the formula is easy to compute, yet often accurate. Consequently work-processing programs like Word often provide the score as part of their statistics. We compute the Flesch reading easy score using GNU Style, a program that has the additional advantage that it also computes several related measures besides. We have used the results of those measures (the Kincaid formula, the automated readability index, the Coleman-Liau formula, the Fox index, the Lix formula, and SMOG-grading) to corroborate our findings but for the ease of exposition we’ll confine ourselves on the Flesch reading easy score here.

Results

Labels

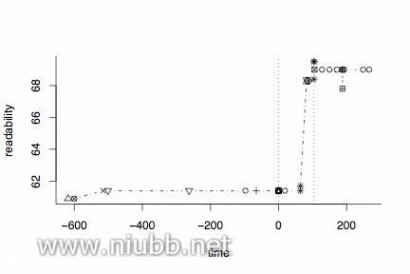

Labeling seems to be one of the most important mechanisms that are used within Simple Wikipedia to make sure that the articles that it contains remain readable. The potential of this mechanism is neatly illustrated in Figure 1. This Figure depicts the evolution of the readability over time of page 3010 – a page aptly entitled “Propaganda”. Readability is based on the Flesch reading easy score and Time is given as the number of days relative to the first occurrence of the tag “unsimple” on the page. In addition, the dotted vertical lines indicate the period during which the

9 page was labelled with the tag “unsimple” and the shapes of the points correspond to the different contributors to the page.

The first thing to notice is the dramatic effect that the tag “unsimple” seems to have on the readability of the page. Before the tag first appears, the readability score of the page hovers around the border between a standard and a fairly difficult level of readability. When the tag is removed, 100 days later, the readability has jumped to the other side of the spectrum, now bordering between a standard and a fairly easy level of readability. Looking at the shapes of the points, a history emerges in which someone wrote the initial page to which others then added a bit without changing much in terms of readability. At some point, day 0, a new contributor comes along and points out that the page is too difficult to read for an article in the Simple Wikipedia collection. The tag “unsimple” then attracts the attention of someone else who actively starts working to improve the readability of the page. As soon as the problem has been remedied, the tag “unsimple” is removed and regular maintenance is resumed.

Moreover, when we look at the distribution of readability scores of all pages that have had the label “unsimple” applied and removed during their existence, on average, the pages have a score of 61.10 when they are first tagged and a score of 70.67 when the tag is removed, while the average score of all pages in the collection is 69.30. Yet, these are average scores and the variance in the distribution of scores is such that it seems more likely that the judgement whether a page is sufficiently simple was based on the participants’ intuition. In that case, the close correspondence of the average scores to the outer ends of the readability spectrum of standard English merely corroborates the Flesch reading easy formula as a measure for readability. In any case, t-tests on the distributions of reading scores reveal that the scores of pages that are

10 tagged are significantly different from the population as a whole when the “unsimple” label is applied and that these scores indistinguishable from the population as a whole at the point when the label is removed. Furthermore, a one-sided paired t-test comparing pages before and after tagging yields a significant improvement in readability – not only for the readability represented by the Flesch reading easy formula, but also for the Kincaid formula, the Automated Readability Index, the Coleman Liau Formula, the Fog index, the Lix formula, and SMOG-grading. With regards to the speed with which “unsimple” pages are transformed into simple one, we find an average improvement almost a half point (0.38) with a confidence of over 95% already after one day and after one week the improvement has become almost full point (0.90) with a confidence of over 99%. Note however that the sample of pages that are affected is relatively small: Among the 27497 pages in the archive, there are only 251 pages that have been tagged as “unsimple” at least once in their livetime. Of these 251 pages, 101, that is about 2/5, had the tag removed at a later stage. In a small number of cases, the Flesch score of a page cannot be determined – for instance when the page has no content – and so there were 245 pages on which we could carry a paired t-test after one day, 242 after one week, and 94 between the first and the last occurrence of the tag.

Eyeballs

We now take a closer look at the process of labelling and the activity it provokes. Who is involved? What is their status within the Simple Wikipedia community? And what level of involvement or experience with the community do they have? First, with respect to the people who declare that a page needs to be improved by attaching the label “unsimple” to it, it turns out that most have had hardly any or no prior involvement with the page that they label. In over 80% of the pages with a tag

11 “unsimple”, the tag was made by a person who had not edited that page before. Where a person had edited before, it had only been one edit in 65% of the cases. Tagging is disproportionately done by administrators, who are responsible for 45% of the tags. Other registered users account for 39% and anonymous users for 16%. This is in stark contrast to the overall distribution of user types in edits where administrators, registered users, anonymous users, and bots are responsible for 18%, 34%, 26%, and 22% respectively. Hence, even though everyone has the right to declare a page “unsimple”, in practice it is a role assumed mainly by people who are part of the “core” group of zealots in the community. The situation is less clear when we look at the edits that occur after the page has been declared “unsimple”, where the respective proportions are 19%, 29%, 33% and 19%, or when we look at the removal of tags with the proportions of 10%, 52%, 37%, and 1% for administrators, registered users, anonymous users, and bots respectively.

In the median, a page is revised 4 times after it has been labelled “unsimple” before the label is removed and a total of 2 authors are responsible for these revisions. Of the 17981 unique authors that contribute to Simple Wikipedia, 640 make a contribution to a page while it is tagged as “unsimple”. For 322 them, the first contribution they made was to a page that was tagged as “unsimple”. All people with the status of administrator contribute to the rewriting of “unsimple” pages while 6 of them actively seek and tag pages. Meanwhile, 451 of the 640 are anonymous users and 301 of the 322 first time users are anonymous.

These questions reverberate with various aspects of the recent literature on peer-based knowledge production. Raymond famously suggested that the quality of open-source software development stemmed from the “many” eyeballs of users and developers, that make bugs “shallow”. Recently, “broadcast” search was studied in the case of

12 R&D, and empirical results tended to reject the “many eyeballs” hypothesis: the number of eyeballs being in this case on the contrary associated with a lower probability of problems broadcasted widely being solved (Jeppesen & Lakhani, 2006). Within Simple Wikipedia, the role of labeller is assumed by a particular group of people that we have identified as “zealots”, while the “unsimple” tag tend to attract the attention of many outsiders who help as good “Samaritans” (Antony et al., 2005). This division of labor is probably more consistent with Mateos-Garcia and Steinmueller’s (Mateos-Garcia & Steinmuller, 2003) insistence upon the roles of editor, integrator and conductor in the process of knowledge production and their mapping to the online sphere. The organization of collective production of information goods, in their view, depends on four kinds of actors: There is, of course, the author, who creates the “information good component”. In addition, there are editors “examining the internal consistency and completeness of the information good component that is to be integrated”; system integrators to “take account of the immediately adjacent information components in order to preserve the integrity of the entire system”; and finally there is an overall co-ordinator or conductor who takes responsibility for the project as a whole.

Bots & Companions

However, the process of labelling or tagging does not always work. Figure 2 shows examples of pages that exhibit common problems. Again the evolution of the readability over time is shown using the Flesch readability formule and time measured in days. The point type indicates the status of the pages, ‘+’ when the label “unsimple” is absent and ‘o’ when it is there. The titles above the plots correspond to the page identifier and page title in the Simple Wikipedia archive. In some cases, like for the pages on “Earth” and “Steel” the label is applied to a page that is already fairly

13 easy to read. In the case of “Earth”, after a considerable delay, the readability increases still further, but in case of “Steel”, the presence of the label seems to have provoked a rather adverse reaction with the page evolving from “very easy” to “fairly difficult.” In other cases, like for the pages on “M-theory” and “FreeBSD”, the label seems to have had the desired effect, but no-one has bothered to remove the label afterwards. In a case like for the page on “Neutrino”, the label didn’t have any effect the first time around, but was noticed and acted upon the second time. However, in a case like the page on “Vagina”, an improvement in readability while it was tagged “unsimple” turned into a rapid deterioration once this reminder wasn’t there anymore. Another case where the label seems to have been removed too early is “Cold-fusion” as it undergoes rapid improvement while it is officially “unsimple” but does not continue this process when the label is removed again and remains “fairly difficult” to understand. Finally, “Sandbox” is the community’s playground and consequently pretty chaotic.

Erratic behaviour in specific cases is not the only problem that hampers the process of labelling. Another problem is that not all badly readable pages are detected. Of the 27246 pages in the archive that have never been labelled as “unsimple”, 2003 (7%) have a maximum Flesch readability score of less than 60 and 897 (3%) have a maximum of less than 50. Most of these pages are probably difficult to read. Conersely, there are cases in which the application of a label is not necessary: there are 3631 pages that evolved from a readability score of less then 60 to a score of more than 70 without ever being labelled.

In a sense, many of these problems would actually be quite easy to address. A solution would be to develop an appropriate bot based on readability scores: this program could suggest pages that might qualify as “unsimple” to administrators

14 and/or label them automatically. Alternatively, the program could notify these zealots when they intend to tag a page that already have a high score. Not least, the program could point towards pages that have been labelled “unsimple” where the readability score has not changed a lot over a long time.

But we would like to suggest that a companion program would partially assume the roles of conductor and integrator that are currently largely absent. Artificial companions are computer programs that act as personal assistants. In the words of Yorick Wilks, who coined the concept, a companion could be seen as a creature that “may look like a furry handbag on the sofa, or a rucksack on the back, but which will keep track of [people’s] lives by conversation, and be their interface to the rather elusive mysteries we now think of as the Internet or Web.” The companion that we envisage is slightly different in that it is less centred around the individual and more in touch with the community, and would therefore itself be developed collaboratively in an open-source way. That is, the companion of a knowledge-based community like Wikipedia could help community members make more valuable contributions by guiding them along according to rules that community members would have themselves defined. We believe that such an editorial companion would be vary valuable for Wikipedia and related communities because it would help them to manage the project more efficiently and consistently.

The step from bot to companion is technically tiny, but there are some important conceptual differences. For instance, the bot is generally associated with a single rule of more technical relevance: typically, a bot would come along at times reformatting pages according to stylistic principles. A editorial companion would be defined as a higher-level bot, and as a set of bots or a botnet, and could always be collaboratively modified to better suit the views of the community as a whole. Furthermore, instead

15 of bots that are mainly used for maintenance of dependencies between Wikipedia projects, a companion would focus on the consistency of the project itself.

The need for something like an artificial companion is apparent in the framework of knowledge-work that was formulated by Mateos-Garcia and Steinmueller: Mateos-Garcia and Steinmueller distinguish between two types of good production: vertical production (systems) and horizontal efforts (collections). “Vertical information good production provides the strongest motives for collaboration because the possibilities of sharing in the externalities generated by other participants are matched by incentives to edit and integrate contributions due to the cumulative dependency of contributions,” while “horizontal efforts, involving complementary dependence, are neither so well developed nor so likely to lure participants from the opportunities offered by self-publication and looser affiliation.” Therefore, voluntary management of the development of collections like Wikipedia is much harder to achieve than voluntary management of the development of systems like Linux as the direct benefit to the individual volunteer is so much lower. Collections like Wikipedia suffer from a relative abundance of authors and artificial companions are needed to help the editors assume the roles of system integrators and co-ordinator.

Finally, implementing a companion would also be a relatively simple solution for Wikipedia in that it would both respect its characteristic decentralized features while ‘simply’ harnessing the creative work of volunteers one step further: beyond the various low-level bots that now exist, to an open-source and more fully integrated companion whose design and implementation would also be the result of the cumulative and decentralized efforts of Wikipedia and related communities.

16 Conclusion

The management and maintenance of collaborative knowledge production is far from trivial. The practice to single out pages that need to be attended works but many pages go undetected and in some cases the tag that call for attention is ignored or even provokes an adverse reaction. On the positive side, we find that relatively straightforward metrics can go a long way to as a way to analyse and monitor the process of tagging. This suggests that it would be feasible to build appropriate bots, and perhaps a companion as a moderator and editorial assistant for the management and maintenance of collections of this kind. Consequently, we plan and hope for contributions in designing prototype companions based on further analysis of readability management in Simple Wikipedia and of quality management in Wikipedia at large. In order to achieve this, we will move from descriptive statistics to models that predict things like the effectiveness of a tag for a given page. Ultimately, these models will embody the goals subscribed to by the community and will turn into companions that help the community achieve those goals. Thus, we believe, could significantly contribute to make knowledge collections like Wikipedia’s more reliable and therefore socially valuable.

References

[Antony et al., 2005] Antony, D., Smith, S. W., and Williamson, T. (2005). Explaining quality in internet collective goods: Zealots and good samaritans in the case of wikipedia. Technical report, Darmouth College, Hannover, NH.

[Beardsley et al., 2005] Beardsley, S. C., Manyika, J. M., and Roberts, R. P. (2005). The next revolution in interactions. McKinsey Quarterly, 4.

[Ciffolilli, 2003] 17 Ciffolilli, A. (2003). Phantom authority, self-selective recruitment and retention of members in virtual communities: The case of wikipedia. First Monday, 8(12).

[Collins-Thompson and Callan, 2005] Collins-Thompson, K. and Callan, J. (2005). Predicting reading difficulty with statistical language models. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 56(13):1448–1462.

[Cross, 2006] Cross, T. (2006). Puppy smoothies: Improving the reliability of open, collaborative wikis. First Monday, 11(9).

[Cunningham and Leuf, 2001] Cunningham, W. and Leuf, B. (2001). The Wiki Way. Quick Collaboration on the Web. Addison-Wesley.

[den Besten et al., 2006] den Besten, M., Dalle, J.-M., and Galia, F. (2006). Collaborative maintenance in large open-source projects. In Damiani, E., Fitzgerald,

B., Scacchi, W., Scotto, M., and Succi, G., editors, Open Source Systems, volume 203, pages 233–244, Boston. IFIP International Federation for Information Processing, Springer.

[Denning et al., 2005] Denning, P., Horning, J., Parnas, D., and Weinstein, L. (2005). Wikipedia risks. CACM, 12(48).

[Duguid, 2006] Duguid, P. (2006). Limits of self-organization: Peer production and “laws of quality”. First Monday.

[Emigh and Herring, 2005] Emigh, W. and Herring, S. C. (2005). Collaborative authoring on the web: A genre analysis of online encyclopedias. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth Hawai’i International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-38).

[Franke and Shah, 32] Franke, N. and Shah, S. (32). How communities support innovative activities: An exploration of assistance and sharing among end-users. Research Policy, 1:157–178.

18

[Gasser et al., 2003] Gasser, L., Ripoche, G., Scacchi, W., and Penne, B. (2003). Understanding continuous design in f/oss projects. In 16th International Conference on Software Engineering and Its Applications, Paris, France.

[Giles, 2005] Giles, J. (2005). Internet encyclopaedias go head to head. Nature, 438:900–901.

[Jeppesen and Lakhani, 2006] Jeppesen, L. B. and Lakhani, K. R. (2006). Broadcast search in problem solving: Attracting solutions from peripheral solvers. Technical Report 2006-10-30, Harvard Business School.

[Lanier, 2006] Lanier, J. (2006). Digital maoism: The hazards of the new online collectivism. Edge, 183.

[Mateos Garcia and Steinmueller, 2003] Mateos Garcia, J. and Steinmueller, W. E. (2003). Applying the open source development model to knowledge work. INK Open Source Research Working Paper 2, SPRU - Science and Technolgy Policy Research, University of Surrey.

[Neus, 2001] Neus, A. (2001). Managing information quality in virtual communities of practice. In Pierce, E. and Katz-Haas, R., editors, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Quality.

[Orlikowski, 2002] Orlikowski, W. J. (2002). Knowing in practice: Enacting a collective capability in distributed organizing. Organization Science, 13(3):249–273.

[Quiggin, 2005] Quiggin, J. (2005). Blogs, wikis and creative innovation. Technical report, University of Queensland.

[Stvilia et al., 2005] Stvilia, B., Twidale, M. B., Smith, L. C., and Gasser, L. (2005). Assessing information quality of a community-based encyclopedia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Quality.

[Surowiecki, 2004] Surowiecki, J. (2004). The Wisdom of Crowds. Doubleday.

19

[Tatum, 2006] Tatum, C. (2006). The case of wikipedia as a distributed knowledge laboratory. In NCeSS conference workshop: Social Science Perspectives on e-Science.

[Winchester, 1999] Winchester, S. (1999). The Surgeon of Crowthorne: A tale of murder, madness and the Oxford English Dictionary. Penguin.

Flesch Reading Ease Score 0-29 50-59 60-69 70-79

80-89

TABLE 1: Measuring Plain English.

Readability Level Very Difficult Fairly Difficult Standard Fairly Easy Easy

20

FIGURE 1: Edits on page 3010 – “Propaganda”.

21

Figure 2 Keeping it simple: A selection of pages

二 : THEYVE GOTTA KEEP IT: PEOPLE WHO SAVE EVERYTHING

1. Most of us have more things than we need and use. At times they pile up in corners and closets accumulate, in the recesses of attics, basements garages. But we sort through our clutter periodical and clean it up, saving only what we really need and giving away or throwing out the excess. This isn't case, unfortunately, with people we call "pack rats" those who collect, save or hoard insatiably, often with only the vague rationale that the items may someday be useful. And because they rarely winnow what they save it grows and grows.

2. While some pack rats specialize in what they collect, others seem to save indiscriminately. And what they keep, such as junk mail, supermarket receipts, newspapers, business memos, empty cans, clothes or old Christmas and birthday cards, often seem to be worthless. Even when items have some value, such as lumber scraps, fabric remnants, auto parts, shoes and plastic meat trays, they tend to be kept in huge quantities that no one could use in a lifetime.

3. Although pack rats collect, they are different from collectors, who save in a systematic way. Collectors usually specialize in one of a few CLASSes of objects, which they organize, display and even catalogue. But pack rats tend to stockpile. Their possessions haphazardly and seldom use them.

4. Our interest in pack rats was sparked by a combination of personal experience with some older relatives and recognition of similar saving patterns in some younger clients one of us saw in therapy sessions. Until then, we, like most people, assumed that pack rats were all older people who had lived through the Great Depression of the 1930s -- eccentrics who were stockpiling stuff just in case another Depression came along. We were surprised to discover a younger generation of pack rats, born long after the 1930s.

5. None of these clients identified themselves during therapy as pack rats or indicated that their hoarding tendencies were causing problems in any way. Only after their partners told us how annoyed and angry they were about the pack rats unwillingness to clean up the growing mess at home did they acknowledge their behavior. Even then, they defended it and had little interest in changing. The real problem, they implied, was their partner's intolerance rather than their own hoarding.

6. Like most people, we had viewed excessive saving as a rare and harmless eccentricity. But when we discussed our initial observations with others, we gradually came to realize that almost everyone we met either admitted to some strong pack-rat tendencies or seemed to know someone who had them. Perhaps the greatest surprise, however, was how eager people were to discuss their own pack-rat experiences. Although our observations are admittedly based on a small sample, we now believe that such behavior is common and that, particularly when it is extreme, it may create problems for the pack rats or those close to them.

7. When we turned to the psychological literature, we found surprisingly little about human collecting or hoarding in general and almost nothing about pack-rat behavior. Psychoanalyses view hoarding as one characteristic of the "anal" character, type, first described by Freud. Erich Fromm later identified the "hoarding orientation" as one of the four basic ways in which people may adjust unproductively to life

8. While some pack rats do have typically “anal” retentive characteristics such as miserliness, orderliness and stubbornness, we suspect that they vary as much in personality characteristics as they do in education, socioeconomic status and occupation. But they do share certain ways of thinking and feeling about their possessions that shed some light on the possible causes and consequences of their behavior.

9. Why do some people continue to save when there is no more space for what they have and they own more of something than could ever be used? We have now asked that question of numerous students, friends and colleagues who have admitted their pack-rat inclinations. They readily answer the question with seemingly good reasons, such as possible future need ("I might need this sometime"), sentimental attachment ("Aunt Edith gave this to me"), potential value ("This might be worth something someday") and lack of wear or damage ("This is too good to throw away") reasons are difficult to challenge; they are grounded in some truth and logic and suggest that pack-rat saving reflects good sense, thrift and even foresight. Indeed, many pack rats proudly announce, "I've never thrown anything away!" or "You would not believe what I keep!"

10. But on further questioning, other, less logical reasons become apparent. Trying to get rid of things may upset pack rats emotionally and may even bring physical distress. As one woman said, "I get a headache or sick to my stomach if I have to throw something away."

11. They find it what to keep and what to throw away. Sometimes they fear they will get rid of something that they or someone else might value, now or later. Having made such a "mistake" in the past seems to increase such distress. "I’ve always regretted throwing away the letters Mother sent me in college. I will never make that mistake again," one client said. Saving the object eliminates the distress and is buttressed by the reassuring thought, "Better to save this than be sorry later."

12. Many pack rats resemble compulsive personality in their tendency to avoid or postpone decisions, perhaps because of an inordinate fear of making a mistake. Indeed, in the latest, edition, of the psychiatric diagnostic bible (DSM-III-R), the kind of irrational hoarding seen in pack rats ("inability to discard worn-out or worthless objects even when they have no sentimental value") is described as a characteristic of people with obsessive compulsive.

13. Some pack rats seem to have a depressive side, too. Discarding things seems to reawaken old memories and feelings of loss or abandonment, akin to grief or the pain of rejection. "I feel incredibly sad -- it's really very painful," one client said of the process Another client, a mental-health counselor, said "I don't understand why, but when I have to throw something away, even something like dead flowers, I feel my old abandonment fears and I also feel lonely."

14. Some pack rats report that their parents discarded certain treasured possessions, apparently insensitive to their attachment to the objects. My Dad went through my room one time and threw out my old shell collection that I had in a closet. It devastated me," said one woman we interviewed. Such early experiences continue to color their feelings as adults, particularly toward possessions they especially cherish.

15. It's not uncommon for pack rats to "personalize their possessions identify with them, seeing them extensions of themselves. One pack rat defiantly sad about her things, "This is me -- this is individuality and you are not going to throw it out!"

16. At times the possessions are viewed akin to beloved people. For example, one woman said, "I can't let my Christmas tree be destroyed! I love my Christmas ornaments -- I adore them!" Another woman echoed her emotional involvement: "My jewelry is such comfort to me. I just love my rings and chains Discarding such personalized possessions could easily trigger fears, sadness or guilt because it would be psychologically equivalent to a part of oneself dying or abandoning a loved one.

17. In saving everything, the pack rat seems to have found the perfect way to avoid indecision and the discomfort of getting rid of things. It works – but only for a while. The stuff keeps mounting, and so do the problems it produces.

18. Attempts to clean up and organize may be upsetting because there is too much stuff to manage without spending enormous amounts of time and effort One pack rat sighed, "Just thinking about cleaning it makes me tired before I begin." And since ever-heroic efforts at cleaning bring barely visible results, such unrewarding efforts are unlikely to continue.

19. At this point, faced with ever-growing goods and ineffective ways of getting rid of the excess, pack rats may begin to feel controlled by their possessions. As one put it. I'm at the point where I feel impotent about getting my bedroom cleaned."

20. Even if the clutter doesn't get the pack rats down, it often irks others in the households who do not share the same penchant for saving. Since hoarding frequently begins in the bedroom, the pack rat's partner is usually the first to be affected. He or she begins to feel squeezed out by accumulated possessions, which may seem to take precedence over the couple's relationship.

21. At first, the partner may simply feel bewildered about the growing mess and uncertain about what to do, since requests to remove the "junk" tend to be ignored or met with indignation or even anger. One exasperated husband of a pack-rat client said: "She keeps her stuff in paper bags all over the bedroom. You can now hardly get to the bed. I tried talking to her about it but nothing seems to work. When she says she has cleaned it out, I can never see any change. I'm ready to hire a truck to cart it all away."

22. As the junk piles accumulate, the partner may try to clean up the mess. But that generally infuriates the pack rat and does nothing to break the savings habit. As the partner begins to feel increasingly impotent, feelings of frustration and irritation escalate and the stockpiled possessions may become an emotional barrier between the two. This situation is even worse if the pack rat is also a compulsive shopper whose spending sprees are creating financial problems and excessive family debt.

23. Children are also affected by a parent's pack-rat behavior. They may resent having the family's living space taken over by piles of possessions and may hesitate to ask their friends over because they are embarrassed by the excessive clutter and disarray. One child of a pack rat said, "As long as I can remember, I've always warned people what to expect the first time they come to our house. I told them it was OK to move something so they would have a place to sit down. "Even the adults may rarely invite non family members to visit because the house is never presentable.

24. Children may also be caught in the middle of the escalating tension between their parents over what to do about all the stuff in the house. But whatever their feelings, it is clear that the children are being raised in an environment in which possessions are especially important and complex emotions.

25. Our clients and other people we have consulted have helped make us aware of the problems pack rats can pose for themselves and those around them. Now we hope that a new study of excessive savers will provide some preliminary answers to a number of deeper questions: What predisposes people to become pack rats, and when predisposes people to become pack rats, does hoarding typically start? Can the behavior be averted or changed? Is excessive saving associated with earlier emotional or economic deprivation? Does such saving cause emotional distress directly or are pack rats only bothered when others disapprove of their behavior? Do pack rats run into problems at work the same way they often do at home?

26. Whatever additional information we come up with, we're already sure of at least one thing: This article will be saved forever by all the pack rats of the world.

From Lynda Warren and Jonnae C. Ostrom, "They've Gotta Keep it: People Who Save Everything," San Francisco Chronicle, "This World," May 1, 1988. Originally published in Psychology Today. Reprinted with permission.

61阅读| 精彩专题| 最新文章| 热门文章| 苏ICP备13036349号-1